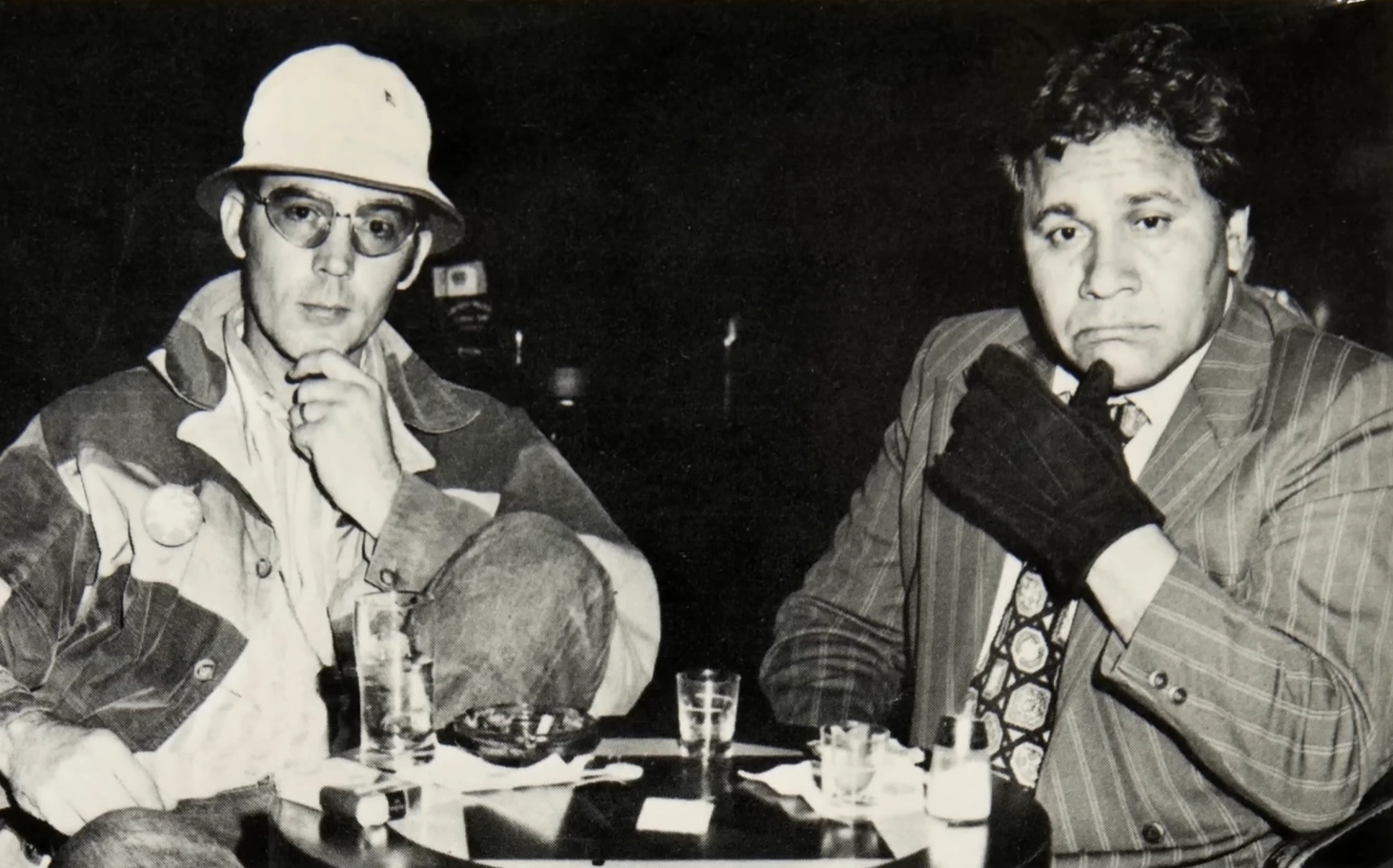

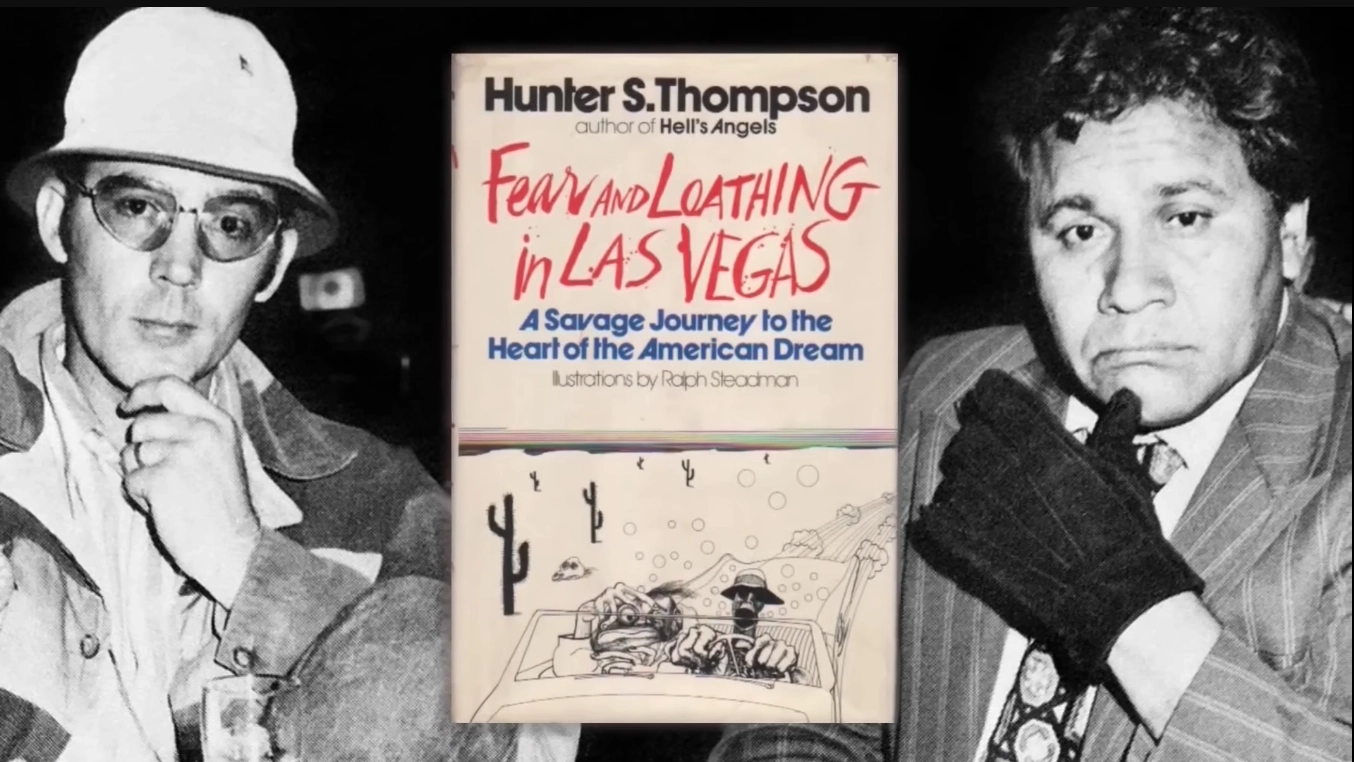

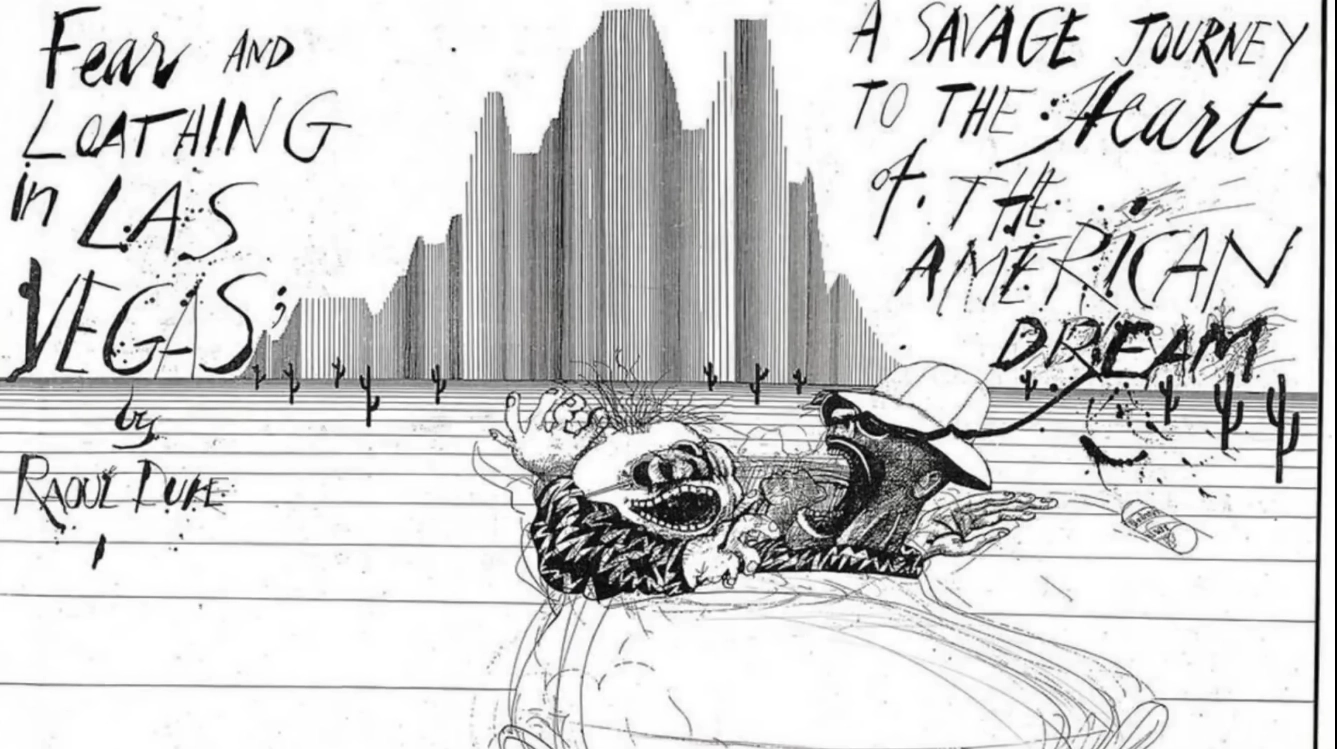

You know the legend. We all know the legend. The maniac in the passenger seat, the "300-pound Samoan" aiming the Great Red Shark toward Las Vegas, fueled by a head full of acid and a desire to find the American Dream. He is Dr. Gonzo, the erratic, knife-wielding sidekick to Hunter S. Thompson’s Raoul Duke [01:00]. But legends have a way of eclipsing the truth, and in the shadow of Thompson’s literary superstardom, a man of equal size and ferocity was lost.

His name was not Dr. Gonzo. He was not Samoan. He was Oscar Zeta Acosta, the Brown Buffalo, and his story is a savage journey all its own [01:54].

From El Paso to the Front Lines

To understand the man who would eventually vanish into the mists of counter-culture mythology, you have to look past the caricature. Born in El Paso, Texas, in 1935, Acosta didn't start as a radical. He was the dutiful son who took on the weight of his family when his father was drafted in World War II [02:49]. He served four years in the Air Force, a young man searching for his place in an America that often refused to see him.

But the fire was always there. He became the first in his family to get a college education, studying creative writing before grinding through night classes at San Francisco Law School. By 1966, he had passed the bar. By 1967, he was in the trenches of East Oakland as an anti-poverty attorney [03:15]. This was not a man built for the sidelines.

The Lawyer, The Activist, The Sheriff?

When Acosta moved to East Los Angeles, he didn't just join the Chicano movement; he became one of its beating hearts. He famously defended the "East Side 13," the organizers of the high school walkouts, cementing his reputation as a warrior for his people [03:52]. The LAPD watched him. The community revered him.

So, naturally, he ran for Sheriff.

It was 1970. Acosta, campaigning with the goal of dissolving the department entirely, went up against the long-serving Peter J. Pitches. He was arrested for contempt of court during the campaign—a badge of honor for a man like him. He lost, gathering 100,000 votes to Pitches' 1.3 million, but the message was sent. The Brown Buffalo was not afraid to charge [04:18].

Fear, Loathing, and the Erasure of Identity

It was the death of journalist Ruben Salazar that brought Acosta and Thompson together in the barrios of East L.A. They were investigating the suspicious nature of Salazar’s death—officially an accident, likely foul play by the police. The paranoia of digging into a police killing in East L.A. became so suffocating that Thompson suggested a break: a trip to Las Vegas to cover the Mint 400 [05:43].

That trip birthed Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. But here is where the tragedy of Oscar Acosta begins. He didn't even know the book was being written until a week before publication. When the lawyers came trembling, afraid of a libel suit from the "erratic" lawyer depicted inside, they missed the point entirely.

Acosta wasn't offended by the drug use. He wasn't fazed by the debauchery. He was outraged that Thompson had called him a "300-pound Samoan." To Acosta, it was an erasure of his Chicano identity, a stripping away of the very cause he fought for [07:07].

He made a deal. He would sign off on the book, but only if a photo of him and Thompson appeared on the dust jacket, clearly identifying him: "Oscar Zeta Acosta, who insists on being identified as Dr. Gonzo." [08:11].

The Vanishing

Acosta used the notoriety to launch his own literary career, publishing Autobiography of a Brown Buffalo and The Revolt of the Cockroach People. He was a lawyer, an activist, and now a celebrated author. He was in the "full crazed flower of his prime" [11:46].

And then, in 1974, he disappeared off the face of the earth.

The last word came from Mazatlán. He spoke to his son, Manuel, on the telephone, telling him he was boarding a "boat full of white snow." Cocaine. After that? Silence [10:27].

For 48 years, the rumors have swirled. Was he killed in a drug deal gone wrong? Did he die in an ambush off the coast of Key Biscayne, piloting a boat through a hail of bullets? Was he seen in Calcutta, or Houston, or running a cigarette boat to Bimini with a silver Uzi in one hand? [12:34].

Thompson hired investigators. They found nothing. The Brown Buffalo had simply vanished into the myth he helped create.

Too Rare to Die

Today, Acosta’s legacy is finally stepping out from the shadow of Dr. Gonzo. His books are back in print, recognized as essential pieces of Mexican-American history [15:48]. A documentary has peeled back the curtain on his life. But the mystery remains.

Perhaps the only way to close the book on Oscar Zeta Acosta is with the words Thompson wrote for him—words that acknowledge the beautiful, terrifying singularity of the man:

"Oscar was one of God's own prototypes, a high-powered mutant of some kind who was never even considered for mass production. He was too weird to live and too rare to die." [16:51]

He may be gone, but the Brown Buffalo still roams in the pages of history, howling old testament gibberish, refusing to be forgotten.